NewsNext Previous

Clarifying the origins of Sima de los Huesos hominins

Analysis of nuclear DNA isolated from hominins from the 430,000 year-old Sima de los Huesos locality in northern Spain, in Atapuerca (Burgos) provides more conclusive evidence of their evolutionary history. The findings are reported in Nature this week. Eudald Carbonell, researcher IPHES, is coauthor of the article.

Until now it has been unclear how the 28 hominin individuals found at the Middle Pleistocene Sima de los Huesos (‘pit of bones’) site were related to hominins who lived in the Late Pleistocene and, in particular, to Neanderthals and Denisovans. A previous report based on analyses of mitochondrial genomes (DNA from the mitochondria) from these specimens suggested a close relationship to Denisovans, which is in contrast to other archaeological evidence, including morphological features that the Sima de los Huesos hominins shared with Neanderthals living in the Late Pleistocene.

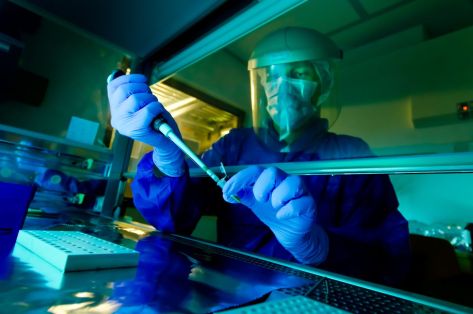

Using very sensitive sample isolation and genome sequencing technologies, Matthias Meyer (Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig, Germany) and colleagues extracted and analyzed nuclear DNA sequences from two specimens from Sima de los Huesos, as well as mitochondrial DNA from one of the two specimens. The nuclear DNA shows that these hominins belong to the Neanderthal evolutionary lineage and are more closely related to Neanderthals than to Denisovans. This finding indicates that population divergence between Denisovans and Neanderthals occurred prior to 430,000 years ago.

Consistent with the previous study, analysis of the mitochondrial DNA supports a closer relationship to Denisovans than Neanderthals, leading the authors to speculate that the mitochondrial DNA seen in Late Pleistocene Neanderthals may have been acquired by them at a later stage, perhaps owing to gene flow from Africa. They propose that retrieval of further mitochondrial and nuclear DNA from Middle Pleistocene fossils could help to further clarify the evolutionary relationship between Middle and Late Pleistocene hominins in Eurasia.